Security (Surveys from the Cape of Good Hope): Jane Alexander @ La Centrale Électrique

BRUSSELS – Through July 21st, La Centrale Électrique of Brussels exhibits the first monographic exhibition in Belgium of the controversial and surprising African artist Jane Alexander, titled Security (Surveys from the Cape of Good Hope). Brussels’ exhibition comes prior to the presentation of the artist’s works at the Museum for Africa Art of New York next winter and features installations, photomontages, and videos about the issue—pivotal in Alexander’s work—of post-colonial South Africa.

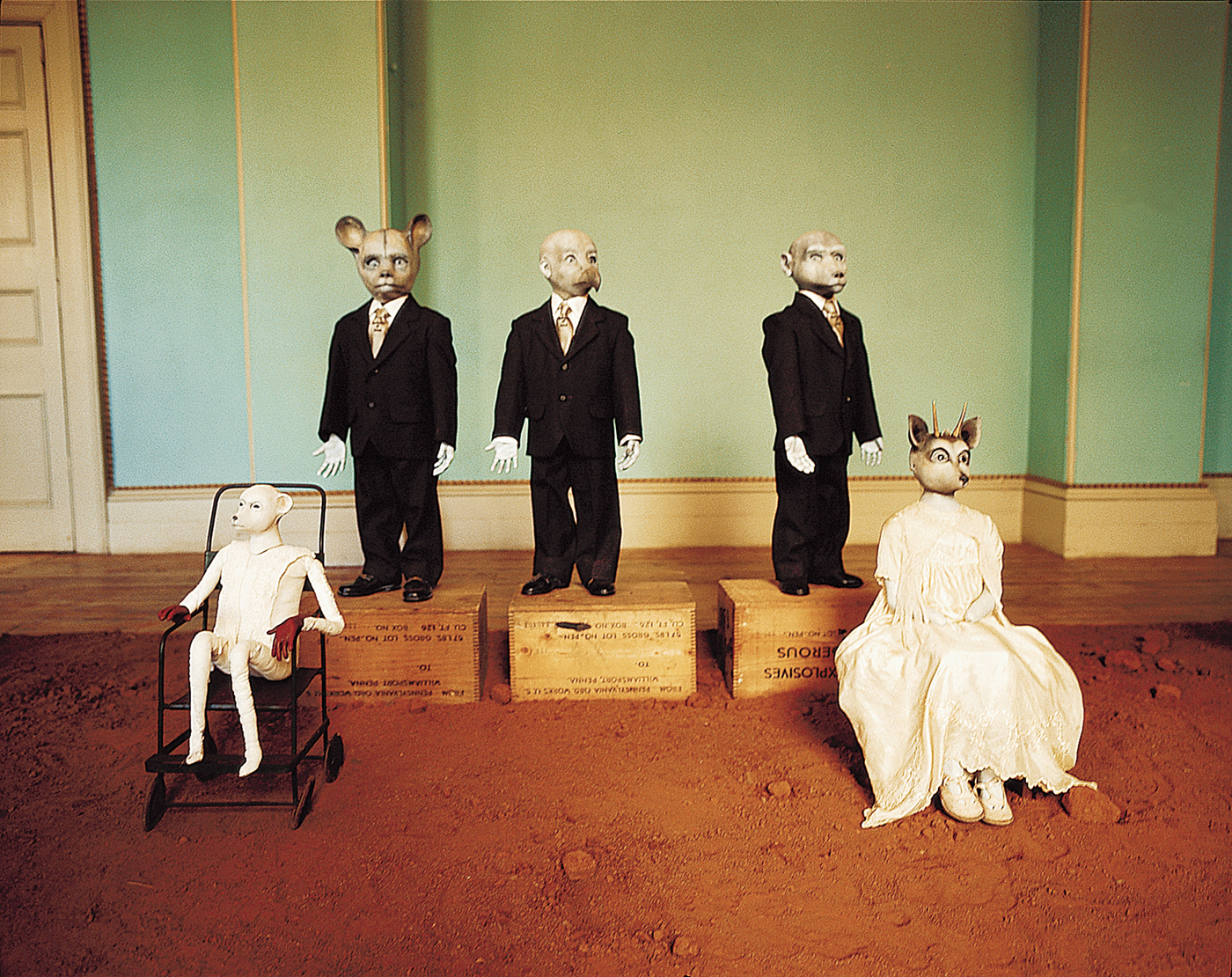

The boundary between humans and animals has been endlessly explored in arts and mythologies all over the world, since prehistory until now. In the case of Alexander, the humanoid figures—“humanimals”, as the curator Pep Subirós calls them quoting a neologism by Julie McGee—carry the message of an evolution that, far from being accomplished and mature, is progressive: “humans-in-the-making.” In this ongoing evolution, man falls back to pursue his most brutal animal impulses, leaving behind the individual in the race for progress and settling into modes of subsistence and survival (as in Bom Boys, 1998).

Born in Johannesburg in 1959, Jane Alexander lives and works in Cape Town. Since her beginnings in the ‘1980s, when South Africa was still under the apartheid regime, the artist has been sensitive to socio-political issues, and to the forms and structures of the exercise of power, oppression and control. In Alexander’s work, the creative exploration of a deeply universal theme departs from the level of the individual and his or her manifold facets, rendering a plain and explicit exposure that reflects the post-colonial past and present of South Africa.

The artist’s universe of human-animals exemplifies the range of motivations that guides human actions—in particular in the case of the exercise of oppression—moving from rationality to instinct, hence realigning mankind within the animal kingdom.

Despite the local background of the themes that underlie the work of the artist—the apartheid, the post-colonial social and political change, the pretended democratization, the new forms of racism and race-based prejudices, and the normalization of social injustice—the work goes beyond thematic localism and engages in a universal consideration of the increasing global obsession with security and new forms of oppression and isolation of ethnic groups and minorities.

The humanoid hybrids convey a sense of depersonalization and annihilation: dog or monkey headed human bodies whose stature is sometimes almost human, sometimes covered with white hoods, naked or dressed with “trouvé” clothes; glassy eyes that stare into the distance. They almost seem the hyper-real materialization of a dreamlike subconscious, seemingly embodying the projection of what we want or are unconsciously pushed to see.

“[T]he viewer is entitled to and does project her or his own interpretation onto the work without explicatory mediation from me other than via a series of recognized or unrecognized keys embedded in or surrounding the presentation of the figure: the title and accompanying caption, sometimes the site, and the elements included in the installation or tableau…” (Alexander 2011).

The tableau African Adventure is a site-specific installation that combines humanoids and several objects such as machetes, sickles, toy tractors, ammunition boxes, diamonds, gold and found objects and clothes. The artists says that the work stems from ten years of observation of the apartheid and from the contradictions experiences in Long Street at Cape Town:

“it shifted from the closed South African scenario of old-times hotels and bars, Group Areas transgressions, children living on the street, and Victorian architecture housing warrens of illicit drug and sex dealers […] to a gentrified concentration of tourist centres, backpacking residences and recreational clubs mixed with the “protection”, the drug and newly legal sex trades, illegal immigrants and refugees from across the continent” (Alexander 2011).

According to the artist, the subject of security in her work originates from the high level of control on private and public spaces in South Africa, with alarms, surveillance cameras, razor-wire perimeters, private security guards and the spread of unlicensed formal and informal weapons. Hence, in her work we often find ominous figures of “custodians,” but also “harbingers” and “settlers,” razor-wire areas, and disturbing figures that watch us from on high. For example, a custodian figure observes the exhibition room sat on a chair in a corner, almost mocking the real keepers of the exhibition and reminding us that control and security are right there, around us.

As the artist reminds us, African art has always been at the centre of a market and a culture characterized by “exotic tastes.” This fact has influenced African artists and has exercised a sort of control on their art. For this reason, too, Alexander amazes: in her work we find an art that speaks about Africa through an artistic language which is universal and extremely contemporary, freed—for better or for worse—of a cultural label typified by commercialization.

Notwithstanding however the series of meanings and interpretations which the variety of symbols lends itself to, Alexander’s work remains cryptic, or better, open. The artist herself reminds us that

“in the end what I intended […] is not important. […] There is no fixed meaning” (Alexander 2011).

References

1. Jane Alexander. “Notes on African adventure and other details,” in Surveys (from the Cape of Good Hope), ed.Pep Subirós. Actar (Barcelona: Museum for African Art, New York, 2011).

Xanadu: Robert Boyd at the Contest Gallery

The exhibition Xanadu, at the Context Gallery of Londonderry from the 19th of October until the 24th of November, is a four-channel epic video installation in which the New Yorker artist Robert Boyd has been working for years. The artist assembled different archivial footage gathered from news broadcasts, internet, documentaries, cartoons and films in four compositions

A Terrible beauty is Coming to Town

To each one his own. Venice, Berlin, London, Paris, Moscow, Prague, Liverpool and many others: each one of them has got its own Biennale of Art. For years now, the capital that gave birth to some of the 20th century’s most revolutionary artists has been lagging behind other leading European cities in terms of contemporary art. It’s finally time to get back on tracks.

bacon's gamble

You visit his studio for the first time. There are tubes of paint everywhere, papers scattered on the floor, a broken mirror, slashed canvases, paint on the walls. Then you see the paintings. At first you notice a figure messed up by a series of spots and deforming lines.